Jan. 31, 2025 - First published by the Canadian Tax Foundation in (2024) 72:4 Canadian Tax Journal. Treaty Provides Unique Benefits To Canadians Migrating To The United States Canadians who emigrate to the United States or elsewhere face many decisions and considerations...

U.S. Tax Laws: A Review of 2017 and a Look Ahead to 2018

Each year at this time, we offer a look back at some of the more significant income tax developments in the United States affecting domestic and international business over the past year and a look ahead to possible U.S. tax developments in the coming year.

Tax Developments in 2017

As we predicted last year, with the election of Donald Trump as president along with Republican control of both houses of Congress, 2017 was a major year for U.S. tax developments. The year began with an executive order by President Trump to reduce the burden of tax regulations and ended with the enactment of surprisingly broad and complex tax reform legislation called the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (the Act).

A brief review of tax developments in 2017 precedes our outlook for 2018.

1. Update on Tax Cases

The long-awaited Tax Court decision in the Grecian Magnesite case – on whether a sale of a partnership interest can generate effectively connected income – finally came down with a taxpayer-friendly result; however, what the Tax Court gave, the Act quickly overrode.

Grecian Magnesite

The IRS has historically taken the position that if a partnership is engaged in a U.S. trade or business and generates effectively connected income (ECI), a portion of the gain recognized by a foreign person when he or she sells an interest in the partnership is itself ECI. The IRS’s opposition was documented in Revenue Ruling 91-32 (published in 1991). Since then, this ruling has generated substantial controversy. In Grecian Magnesite, Mining, Industrial and Shipping Co. S.A. v. Commissioner, the Tax Court held in favour of the taxpayer, agreeing with the taxpayer’s position that the statutory language of section 741 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the Code) trumps the position of the IRS on this issue, and holding that the sale of an interest in a partnership that holds non-FIRPTA ECI assets does not give rise to ECI. As discussed below, however, the Act nullified the Tax Court’s holding by enacting legislation that specifically treats a portion of the gain on a disposition of such an interest in a partnership as effectively connected income.

For a further discussion of the Tax Court’s holding in the Grecian Magnesite case, see U.S. Tax Court Exempts Gain on Sale of Interests in ECI-Generating Partnerships.

2. Administrative Developments

During his campaign, President Trump promised to eliminate burdensome regulations. In furtherance of that promise, he issued an executive order in early 2017. Correspondingly, the Secretary of the Treasury (Secretary) identified eight regulations (the June Report) to be reviewed, and in October 2017, provided final recommendations. Although a full analysis of the Secretary’s recommendations is beyond the scope of this discussion, the more significant projects are described below.

For a more detailed discussion of the summary below, see U.S. Treasury Will Scale Back Debt-Equity and Certain Other Regulations.

Intercompany Debt-Equity Regulations

In 2016, the Treasury had issued lengthy temporary and final regulations on the treatment of certain debt as equity, including (i) per se recasting as equity of certain debt issued by a corporation to a related party (the distribution rules) and (ii) extensive documentation requirements (the documentation rules). Although the IRS had already announced a one-year delay in application of the documentation rules, the October pronouncement actually suggested revoking such rules in their entirety and publishing more limited rules. Despite acknowledging that the distribution rules may also be overly broad, the Treasury decided to delay any further changes.

Foreign Goodwill Regulations

Section 367 of the Code generally triggers gain on outbound asset transfers with an exception for active foreign businesses. Historically, foreign goodwill and going-concern value could be transferred under that exception. Final regulations issued in 2017 eliminated the exception for foreign goodwill and going-concern value. Although in October, the Treasury announced that it might have permitted outbound transfers of foreign goodwill and going-concern value, the Act eliminated the active foreign business exception all together.

Regulations on Treatment of Partnership Liabilities

In 2016, the Treasury issued regulations expanding the disguised-sale rules of section 707 of the Code by limiting a partner’s ability to receive tax-free, debt-financed distributions. In addition, the 2016 regulations blocked the use of so-called bottom-dollar guarantees (which otherwise permit a partner to be allocated a greater share of a non-recourse liability even though the partner was not under the guarantee from the first dollar of debt) because they lack significant non-tax business purpose. In October, the Treasury announced that further study is warranted, and the Treasury is considering revoking the 2016 regulations other than those pertaining to bottom-dollar guarantees.

Proposed Family Transfer Regulations

Under section 2704 of the Code, taxpayers may be limited in reducing the fair market value of an interest in a family-controlled entity for estate and gift tax purposes on the basis of non-commercial restrictions on the ability to dispose of or liquidate such entities. The proposed regulations would have removed discount opportunities, but the Treasury has now determined that the proposed regulations would subject taxpayers to burdensome compliance obligations, and they will be withdrawn.

Temporary Regulations on Certain Transfers of Property to Regulated Investment Companies and Real Estate Investment Trusts

Prior to the issuance of temporary regulations under the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (PATH Act), property could be transferred tax-free to a real estate investment trust. Temporary regulations issued under the PATH Act prevent spinoffs that could accomplish that objective. In October, the Treasury announced that it will reduce the scope of the temporary regulations, which were acknowledged to be potentially overbroad.

3. Tax Legislation

The key U.S. tax development of 2017 was, of course, the tax reform, which is primarily applicable to tax years beginning after December 31, 2017, and will no doubt have a significant impact on the U.S. taxation of businesses and individuals in the United States and Canada and throughout the world, as well as cross-border (including Canada-U.S.) transactions and activity.

Of notable importance, the Act contains no general grandfathering of current structures. Therefore, taxpayers need to consider how their structures are affected by the provisions outlined below, which generally apply to income earned and payments made after December 31, 2017.

By way of background, on November 16, 2017, House Republicans passed an initial tax reform bill (House Bill), and on December 2, 2017, Senate Republicans passed their version of the tax reform bill (Senate Bill), which followed some but not all of the provisions of the House Bill. On December 15, Senate Republicans and House Republicans, looking to come through on a major legislative victory for their base, released a joint conference committee report (Report) that was, with some minor changes, delivered to and signed by the President on December 22, 2017.

For an additional discussion on the summary below, see Republicans Poised to Enact Transformative U.S. Federal Tax Reform. The discussion below is intended to highlight certain important aspects of the Act with an emphasis on international matters and likely business concerns.

Key Provisions Affecting Individuals

These provisions generally expire for tax years beginning after December 31, 2025:

- Income Tax Rates. The Act lowers the top rate slightly to 37%, leaves capital gains rates and qualifying dividend rates (each 20% plus the 3.8% net investment income tax that was not eliminated by the Act) intact and does not reduce the number of brackets.

- No Repeal of the Alternative Minimum Tax. In a departure from the House Bill, the Act retains the alternative minimum tax, but increases the phase-out exemptions to $1 million for married taxpayers filing jointly ($500,000 for single taxpayers).

- Home Mortgage and State and Local Tax Deductions. The Act limits home mortgage interest deductions to interest paid on loans of up to $750,000 (down from $1 million under prior law and the Senate Bill, but up from the $500,000 proposed in the House Bill). It also eliminates deductions for state and local taxes unless paid or accrued in carrying on a trade or business, except that individuals generally may deduct up to $10,000 of state and local income, property or sales taxes.

- Qualified Equity Grants. For stock attributable to options exercised or restricted stock units (RSUs) settled after December 31, 2017 (including with respect to such options or RSUs granted prior to January 1, 2018), if a proper election is timely made, the Act permits deferral of gain on “qualified stock” for up to five years from the date such gain would otherwise have been includible in income. In the absence of this election, employees (subject to certain exceptions and limitations) generally are subject to tax on exercise with respect to stock options or upon settlement (i.e., conversion into shares or cash) with respect to RSUs (or, in either case, if later, the first year for which such stock becomes vested). Qualified stock is stock of a corporation if (i) no stock of such corporation is readily traded on an established securities market during any preceding calendar year, and (ii) such corporation has a written plan under which, in such calendar year, not less than 80% of all employees that are U.S. service providers are granted stock options or RSUs.

- Estate Tax. The Act doubled the estate, generation-skipping and gift tax exemption (from $5 million for individuals and $10 million for married couples to $10 million and $20 million, respectively, in each case adjusted for inflation) for transfers through December 31, 2025. (Non-residents would not benefit from these changes unless a treaty applies.)

Key Provisions Affecting Businesses

- Corporate Tax Rates. The Act immediately and permanently reduced the federal corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%. Some pass-through entities are expected to convert to corporate status, but those entities must avoid federal penalty taxes on excess passive income and unnecessary profit accumulation.

- Pass-Through Business Tax Rates. For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2026, individuals who do business through pass-through entities (e.g., S corporations, sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies treated as partnerships for tax purposes) may qualify for a new 20% deduction. The deduction generally is limited to 50% of the taxpayer’s share of wages paid by the pass-through entity (or, if greater, 25% of such wages plus 2.5% of the unadjusted basis (determined immediately after an acquisition) of all qualified property (generally, tangible property of a character subject to deprecation that is held for use in a trade or business and used in the production of business income) and is not available for taxpayers engaged in specified service businesses (e.g., lawyers, accountants); however, that these limitations generally do not apply to taxpayers with taxable income not exceeding $157,500 ($315,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly). Moreover, the Act provides that trusts and estates are eligible for this new deduction. This provision permits a top marginal tax rate of 29.6% with respect to qualifying income.

- Accelerated Cost Recovery. The Act provides for 100% immediate expensing of certain property placed in service after September 27, 2017, but prior to January 1, 2023. For property placed in service on or after January 1, 2023, the Act gradually phases out the portion of the property that can be immediately expensed. The Act does not require that the original use of the property commence with the taxpayer (as long as the taxpayer did not previously use the property).

- Interest Deductibility Limitations. The Act replaced the former “earnings stripping” rules (including an elimination of the 1.5 to 1 debt-to-equity ratio safe harbour) with a limit of 30% of EBITDA (down from 50%) for taxable years beginning prior to January 1, 2022. For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2021, the interest deductibility limitation will be based on 30% of EBIT. The new rules exempt businesses with average gross receipts of $25 million or less and specified trades or businesses, including electing real property businesses. Unlike prior law, the new limitation applies whether or not the interest is paid to a related party. In addition, the limitations apply to partnership interest expense and are determined at each partnership level (presumably without duplication of limitations or allowances). Disallowed interest is carried forward indefinitely. The Act does not include further broad limitations proposed in the House Bill and Senate Bill for large corporate groups.

- Modification of Net Operating Loss Deduction. For net operating losses arising in taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017, the Act limits the deduction of a net operating loss to 80% of the taxpayer’s taxable income (determined without regard to the net operating loss). In addition, net operating losses can be carried forward (but not back) indefinitely (as compared to 2 years back and 20 years forward for losses arising before the new rules took effect).

- Limit on Like-Kind Exchanges. The Act eliminates the possibility of deferring tax on simultaneous and deferred asset swaps for properties other than real estate.

- Carried Interests. Under pre-Act law, a service provider that received a partnership interest in connection with the performance of services for the partnership (i.e., a carried interest) was generally entitled to long-term capital gain treatment (and a reduced rate of 20% plus the 3.8% net investment income tax) on the disposition of the partnership interest if the service provider held the partnership interest for more than one year if the character of the underlying profits of the partnership is long-term capital gain. The Act has created a three-year holding period requirement that must be satisfied in order for carried interest holders to receive long-term capital gain treatment.

- Narrowing of Contribution to Capital Limitation in House Bill. Under a provision of pre-Act law, contributions to capital of a corporation were generally excluded from the gross income of that corporation. The House Bill proposed to eliminate this provision for contributions to capital where the fair market value of the contribution exceeded the fair market value of the equity received. The Act did not follow the House Bill’s proposal.

- Private Activity Bonds. The House Bill surprised many tax practitioners by repealing the tax-exemption for interest on private activity bonds, a common mechanism for financing large-scale infrastructure projects with private funds. The Act followed the Senate Bill by leaving the tax exemption for private activity bonds in place. The Act does, however, include provisions from the House Bill that eliminate the exclusion for interest on advance refunding bonds and prevent the issuance of tax-credit and direct-pay bonds.

- Renewable Energy Credit. The House Bill contained certain provisions that would have adversely affected the availability of, and benefits attributable to, certain renewable energy credits, including (i) a reduction of the production tax credit to 1.5 cents per kilowatt hour and an elimination of the adjustment for inflation and (ii) a requirement that projects that begin construction maintain a continuous program of construction beginning with commencement and ending when the property is placed in service, which requirement may have been different than provided by existing IRS guidance and may have had retroactive effect. The Act did not include the provisions of the House Bill.

Key International Provisions

Partial Territorial Tax System

- Participation Exemption. Under the prior U.S. system of worldwide taxation, the United States taxes the income earned by U.S. corporations and their foreign subsidiaries wherever such income is earned, either at the time it is earned or when it is later distributed. In order to shift the United States toward a territorial system of taxation in which income generally is only subject to U.S. tax to the extent it is earned in the United States, the Act exempts from U.S. tax 100% of any foreign source dividends paid by a foreign corporation to a U.S. corporate shareholder that holds at least 10% of the stock of such foreign corporation, but does not exempt unincorporated branches, certain “hybrid dividends” or so-called subpart F income or GILTI (discussed below). This exemption applies only to a domestic corporation that satisfies a 365-day holding period with respect to the stock on which the dividend is being paid. Foreign tax credits attributable to exempt dividends are disallowed.

- Forced Repatriation of Previously Deferred Foreign Earnings. For the last taxable year of an applicable foreign corporation that begins before January 1, 2018, the Act requires U.S. persons (individuals and corporations) owning 10% or more of a controlled foreign corporation and specified foreign corporations to include in income previously (post-1986) deferred earnings. The tax can be spread for up to eight years at a 15.5% rate if such earnings were previously held in the form of cash or other short-term assets, or an 8% rate otherwise. A foreign tax credit may be available for a portion of the foreign income taxes associated with the forced income inclusion. Although U.S. individuals are also subject to the forced repatriation provisions, they are not eligible for the “going-forward” participation exemption regime.

Controlled Foreign Corporations and Subpart F Regime. The Act generally retains the subpart F income regime with certain modifications. The key modifications are as follows:

- The definition of “controlled foreign corporation” (CFC) is expanded by (i) expanding the stock attribution rules for purposes of determining whether a foreign corporation is a CFC by treating a U.S. corporation as owning stock of a foreign corporation held by its foreign shareholders and (ii) expanding the definition of “United States shareholder” to include U.S. persons that own stock representing 10% of the value of a foreign corporation (as opposed to just 10% of the voting power as under pre-Act law).

- The pre-Act requirement that a corporation be a CFC for at least 30 consecutive days for a United States shareholder to be required to include its share of subpart F income has been eliminated.

- In addition, certain taxpayer-friendly modifications that were included in the House Bill and/or the Senate Bill were not included in the Act, such as (i) the proposed repeal of the provisions that currently tax U.S. corporate shareholders on the untaxed earnings of CFCs to the extent that those earnings are reinvested in United States property (e.g., U.S. real estate, tangible property located in the United States or obligations of U.S. affiliates), which seems odd in light of the Act’s switch to a territorial tax system; (ii) the proposal to make the CFC-look-through exception permanent; and (iii) a provision that would have allowed a CFC to distribute appreciated intangible property to a corporate U.S. shareholder without triggering a current income inclusion to the shareholder.

Foreign Tax Credits. Although, as discussed above, a foreign tax credit is permitted to offset the tax on forced repatriation of deferred foreign earnings (reduced on the basis of the permissible deduction with respect to such inclusion), no foreign tax credit is permitted with respect to any taxes paid or accrued on a dividend that qualifies for the participation exemption deduction. However, as the participation exemption deduction does not apply to branches and subpart F income, foreign tax credits for taxes paid with respect to foreign earnings attributable to a branch or resulting from subpart F income can generally still be offset by foreign tax credits.

Current Year Inclusion of “Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income.” The Act departed from the House Bill and took an approach more similar to the Senate Bill by adopting a current year inclusion (in a manner similar to subpart F income) by a U.S. shareholder of a CFC of the U.S. shareholder’s pro rata share of the CFC’s global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI). GILTI generally refers to the excess of the CFC’s taxable income over 10% of the CFC’s aggregate adjusted basis in its depreciable tangible property. For corporate U.S. shareholders, the Act permits a deduction equal to 50% of the GILTI otherwise includible in income. For tax years beginning after 2025, the GILTI deduction is reduced to 37.5%.

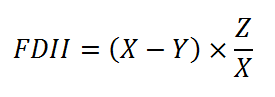

Foreign Derived Intangible Income Deduction. In addition, quite apart from the CFC-related GILTI deduction, the Act permits a deduction for U.S. corporations equal to 37.5% of certain “foreign-derived intangible income” (FDII). For tax years beginning after 2025, the FDII deduction is reduced to 21.875%. FDII refers generally to income that a U.S. corporation receives from foreign persons for sales of property or the performance of services for use outside the United States. In determining FDII, the Act uses a complex formula that essentially operates as follows:

X = USCo's net income (excluding GILTI, certain CFC, foreign branch and domestic oil and gas income)

Y = 10% return on USCo's basis in its tangible depreciable property

Z = USCo's income from sales of property or provision of services outside the United States

The net effect of this provision and the proposed corporate tax rate reduction to 21% is to create a “patent-box” type of concession under which U.S. corporations that export goods or services or that license outside the United States will be subject to a reduced tax rate of 13.125% (increased to 16.406% for tax years beginning after 2025) on income attributable to their export activities.

Base Erosion Minimum Tax. The Act again departed from the House Bill, which included a 20% excise tax on certain U.S. source payments, and instead adopted the “base erosion minimum tax” provision of the Senate Bill (with some adjustments). The base erosion minimum tax provision is imposed on “base erosion payments” paid or accrued by a taxpayer to a foreign related person (defined on the basis of a broad 25% test). Basically, certain U.S. companies making deductible, depreciable or amortizable payments to foreign related persons may have to pay the excess of (i) 10% (up to 12.5% for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2025) of its modified taxable income (determined without regard to such payments) over (ii) such corporation’s regular tax liability. This provision applies to corporations subject to U.S. net income tax with average annual gross receipts of at least $500 million if such corporation’s base erosion payments are at least equal to 3% of the corporation’s total deductions for the year. In most instances, this provision will not apply to cross-border purchases of inventory includible in cost of goods sold (certain cross-border inventory purchases from “surrogate foreign corporations” will be treated as base erosion payments).

Anti-Hybrid Rules. The Act also contains a provision that disallows a deduction for related-party interest or royalties under a hybrid transaction (i.e., a transaction under which a payment is treated as interest or royalties for U.S. tax purposes, but is not treated as such under the tax law of the jurisdiction of the recipient) or involving a hybrid entity (i.e., an entity whose treatment as a pass-through entity or corporation for U.S. tax purposes differs from its treatment for foreign tax purposes) if (i) there is no corresponding income inclusion to the related party under local tax law or (ii) the related party is allowed a deduction with respect to the payment under local tax law. The provision grants regulatory authority to the extent necessary to carry out the purposes of this provision with respect to branches and domestic entities. This provision seems to target certain cross-border financing structures, including those commonly used in the Canada-U.S. context, such as “repo” transactions, and would potentially deny deductions for interest paid in connection with such a structure. Moreover, the Act does not contain any grandfathering rule with respect to this anti-hybrid provision and therefore may have an impact on covered payments made after 2017 with respect to cross-border financing structures that are already in place.

Sale of Certain Partnership Interests Characterized as Effectively Connected Income. The Act reverses the Tax Court decision in Grecian Magnesite (discussed above), which held that an interest in a partnership sold by a foreign party constitutes a separate capital property and does not entail a sale of the underlying assets of the partnership. Under the Act, gain or loss from the sale or exchange by a non-U.S. person of an interest in a partnership engaged in a U.S. trade or business is treated as effectively connected income subject to U.S. tax if a sale by the partnership of all of its assets would give rise to effectively connected income. The Act further provides that the transferee of the partnership is required to withhold 10% of the amount realized. Although the tax applies to transactions taking place on or after November 27, 2017, the withholding provision applies only to transactions taking place after December 31, 2017.

Repeal of Active Trade or Business Exception. Under prior law, section 367 of the Code, which generally triggers gain on outbound asset transfers, contained an exception for outbound transfers of active foreign businesses. The Act eliminated the gain recognition exception for outbound transfers of active foreign businesses.

Outlook for U.S. Tax Developments in 2018

The most significant development that will have an impact on the U.S. tax landscape for 2018 is, of course, the Act. We should expect this not only to affect guidance from the IRS and the Treasury but also to generate significant activity as taxpayers and their advisers digest the provisions of the Act and determine how to best implement tax strategies in light of the new tax laws.

1. Tax Planning Considerations

Although the passage of the Act at the end of December with a general effective date of January 1, 2018, and no grandfathering of pre-Act structures left little time for taxpayers and their advisers to implement tax strategies to take advantage of (or minimize the adverse impact of) the provisions contained in the Act, some activity may have taken place at the end of 2017 or should be expected during the early part of 2018.

Lower Tax Rates

Near the end of 2017, as the likelihood increased that tax reform would include lowering both corporate and individual rates, many taxpayers may have deferred until 2018 transactions that would result in a recognition of gain (particularly for corporate taxpayers). As a result, we expect to see a flurry of transactions at the beginning of 2018 that were delayed until the Act was passed and the new lower tax rates became effective.

Restructuring to Access Corporate Tax and Participation Exemption

In 2018, in light of the reduction of the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% and the availability of the participation exemption deduction being limited to U.S. corporate shareholders of foreign corporations, we expect to see taxpayers incorporating flow-through businesses and non-corporate holdings of interests in CFCs into domestic holding corporations in order to access lower corporate tax rates and the participation exemption deduction; however, taxpayers and their advisers will need to keep their eyes on any potential future changes in law to address such structures, as well as the personal holding company and accumulated earnings tax rules. Notwithstanding the reduced corporate tax rate and the switch to a partial territorial system of taxation, U.S. corporate taxpayers may still benefit from holding offshore operations through CFCs if the local country tax rate is below 21%, although GILTI may reduce the benefit otherwise available.

Increased Gift Tax Exemption

As people may have been anticipating an increase in the gift tax exemption under the Act, taxpayers may have deferred taxable gifts until 2018 to take advantage of the doubled gift tax exemption (as compared with pre-Act law). Again, we expect to see gifts being made in the early part of 2018 that may have been deferred to benefit from the increased exemption.

2. Partnership Audit Rules

The new partnership audit rules initially set forth in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 officially became effective for taxable years beginning after January 1, 2018. These sweeping changes to the partnership audit rules and the way in which audit adjustments are imposed on partnerships and partners are significant. If partnerships, partners and their advisers have not yet considered how they may be affected by these revised partnership audit rules, they will now want to review and modify, as appropriate, their partnership agreements.

3. Expected IRS and Treasury Guidance

Revisions to Burdensome Regulations

As noted above, in 2017, the Trump administration promised to reduce the burden of tax regulations by identifying and providing recommendations on eight regulations identified as potentially being overly burdensome to taxpayers. In connection with the recommendations set forth by the Secretary in October 2017 (and as included in the 2017-2018 Priority Guidance Plan), the Treasury announced that additional guidance would be forthcoming to replace, revise or simplify certain identified regulations. For example, guidance that we should expect to see in 2018 includes the following:

- replacing the documentation rules of the debt-equity regulations with a more limited set of rules (and possibly considering whether any revisions should be made to the distribution rules);

- formally revoking the 2016 partnership liability regulations (other than the bottom-dollar guarantee regulations, as discussed above) and the proposed family transfer and valuation regulations (as discussed above); and

- reducing the scope of the PATH Act regulations that potentially prevent spinoffs from being used to transfer property tax-free to a real estate investment trust.

Guidance Regarding Implementation of the Act

As a result of the sweeping tax reform resulting from the passage of the Act at the end of 2017, we expect that the IRS and the Treasury will be very busy in 2018 issuing guidance under the Act. The IRS has already commenced publishing notices under the new tax reform legislation, including one that suspends the requirement of withholding with respect to dispositions of certain publicly traded partnership interests that generate effectively connected income (see IRS Notice 2018-8). Another one provides guidance for determining the amount required to be included in a U.S. shareholder’s gross income by reason of the Code’s section 965 mandatory repatriation rules (see IRS Notice 2018-7).

As an initial area for needed guidance, the IRS will have to quickly publish new withholding tables reflecting the new provisions and tax rates in the Act. In addition, many provisions of the Act either permit the Treasury to clarify or obligate the Treasury to provide regulatory guidance regarding the statutory provisions of the Act. For example, the anti-hybrid rules of the Act specifically state that the Secretary shall issue regulations that may be necessary to provide (i) rules for treating certain conduit arrangements involving hybrid transactions or entities as subject to the anti-hybrid rules, (ii) rules applying the anti-hybrid rules to branches or domestic entities and (iii) rules applying the anti-hybrid rules to certain structured transactions. The provision of the Act that treats certain dispositions of partnership interests as giving rise to ECI and obligates transferees to withhold tax in connection therewith indicates that regulations may be issued to provide exceptions to the withholding obligations of transferees of such a partnership interest. This guidance will be of particular interest to both transferors and transferees of partnership interests as the broad drafting of this provision imposes a withholding obligation that may result in a transferee of a partnership withholding tax in situations in which the transferor of the partnership interest would not be expected to owe any U.S. tax on the transfer.

Additional Guidance

In December, the IRS released regulations relating to the new partnership audit regime (discussed above), which went into effect on January 1, 2018. Under the new regime, the IRS can assess taxes and penalties against partnerships directly, instead of being required to audit the individual partners. The regulations released during December include the following: provisions allowing an audited partnership to push adjustments out to its partners in tiered partnership structures; procedures for obtaining judicial review of partnership audits in federal court; and rules for small partnerships to elect out of the new partnership audit regime. Further guidance is expected on the partnership audit rules in 2018 (which has been included as a separate project under the 2017-2018 Priority Guidance Plan).

The IRS has also issued regulations that allow taxpayers to use mark-to-market accounting to report capital gains and losses with respect to investments denominated in a foreign currency. The provisions include rules on how foreign currency gains of a CFC can qualify for the business needs exclusion and how a CFC should account for foreign currency gains and losses relating to hedging transactions.

Conclusion

With the enactment of transformative U.S. tax reform and the implementation of sweeping changes regarding the partnership audit rules (each of which generally became effective January 1, 2018, and each requiring significant guidance from the IRS and the Treasury), taxpayers, their tax advisers and the Treasury and the IRS will certainly need to analyze and carefully consider the impact of these new tax laws. Adding to the already heavy demands of the IRS and the Treasury, the regulatory revisions under the President’s executive order to reduce tax regulatory burdens (discussed above) and the additional guidance to be provided under the ambitious 2017-2018 Priority Guidance Plan, the Treasury and the IRS will likely be making exhaustive efforts, and be under significant pressure, to provide guidance to taxpayers in a timely fashion. Although the timely provision of guidance is important for taxpayers seeking clarity on the application of these new complex tax provisions, recent and potential future cuts to IRS funding may significantly impede the ability of the IRS to administer the tax rules and provide taxpayer guidance in a timely manner. We query the extent to which the need for guidance, coupled with cuts to funding, may adversely affect the IRS’s ability to attend to its enforcement and collection duties, including audits, appeals and litigation.

Finally, it is worth noting that although the United States has not signed on to the OECD’s BEPS proposals and has expressed little interest in participating in BEPS, the Act has taken a rather BEPS-heavy approach to U.S. tax reform, including through the imposition of a broader interest deductibility limitation and a comprehensive limitation of deductions attributable to the use of hybrid entities or hybrid instruments.

Davies is pleased to welcome our new partner and co-author of this article, Bobby Sood, to the firm. With 19 years of experience in the Tax Services Division at the Department of Justice, Bobby brings a wealth of knowledge and specialized expertise to our team of 11 industry-leading tax dispute lawyers.

Read our Canadian Tax Review and Outlook.

Key Contacts

Related

Dec. 19, 2024 - Despite a strong start to the year, activist activity in Canada in 2024 tapered to pre-pandemic levels. This reversion to more historic annual totals follows a notable resurgence of shareholder demands directed at Canadian public companies in 2023, when shareholder engagement reached its...